December 21, 2020

Karen L. Amendola, Ph.D

Chief Behavioral Scientist

Karen L. Amendola, Ph.D

Chief Behavioral Scientist

Stories about police use of excessive force continue to appear in local and national news headlines. Community-police relationships continue to be strained by these incidents, many of which have been captured on camera and circulated in media. Witnessed and recorded incidents have reportedly led to a loss of trust in the police1 and for calls to defund local police departments. In a post-2020 era, public protestors are calling for replacing police responses with alternative, non-police emergency service members, such as social workers or mental health professionals, with the intent being better outcomes for all parties involved. The emergence of Integrating Communications, Assessment, and Tactics (ICAT) training is, to a great extent, an outgrowth of this strong sentiment across the country, gaining traction after the shooting of Michael Brown.2

Strengthening Community Policing and Trust

In 2015, the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing issued its report with recommendations to strengthen community policing and trust among law enforcement officers and the communities they serve.3The report showcased the disparity between the level of confidence in law enforcement among various communities while including a special emphasis on de-escalation—a technique used to reduce the potential for a conflict to become more volatile or violent.3 Pillar 2 of the report, which focused on Policy & Oversight, Action Item 2.2.1 stated, “Law enforcement agency policies for training on use of force should emphasize de-escalation and alternatives to arrest or summons in situations where appropriate.”3 While the statement is general enough to allow room for interpretation and adaptation to local community preferences and needs, it was the subject of much discussion among police leadership as it was not adequately defined.

Calls for De-Escalation

In 2015, after 18 months of research, the Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) released its Guiding Principles, calling for de-escalation, particularly in situations involving persons with mental illness and cases where persons did not have access to firearms.4 The report challenged conventional thinking on police use of force and became the impetus for launching the ICAT training program the following year. Developed by PERF with input from hundreds of police professionals from all across the United States, ICAT’s mission stated, “Patrol officers will learn to safely and professionally resolve critical incidents involving subjects who may pose a danger to themselves or others but who are not armed with firearms. Reducing the need to use deadly force, upholding the sanctity of life, building community trust, and protecting officers from physical, emotional, and legal harm are the cornerstones of ICAT.”2 ICAT reinforced using the Critical Decision-Making (CDM) Model that helped officers make safe and effective decisions, assess situations, and document and learn from their actions.2 PERF’s ICAT training was supported by the input of police practitioners from the across the country and abroad, and was developed over time with the support of the Motorola Solutions Foundation.

Although ICAT was an important step toward addressing this sensitive issue, no de-escalation training curriculum or model, including ICAT, had been formally evaluated to assess its impact on use of force outcomes until this year. As such, police executives lacked the necessary evidence to support or defend implementation of training as a means for reducing excessive force.

But. . . Does De-Escalation Training Actually Lead to Force Reduction?

Earlier this year, in a systematic review of research on de-escalation across fields (mostly in the fields of nursing and psychiatry), Engel and colleagues (2020) found that de-escalation training produced slight to moderate impacts. However, they concluded that most research on this topic was of questionable quality, calling for high-quality research on de-escalation in policing.5

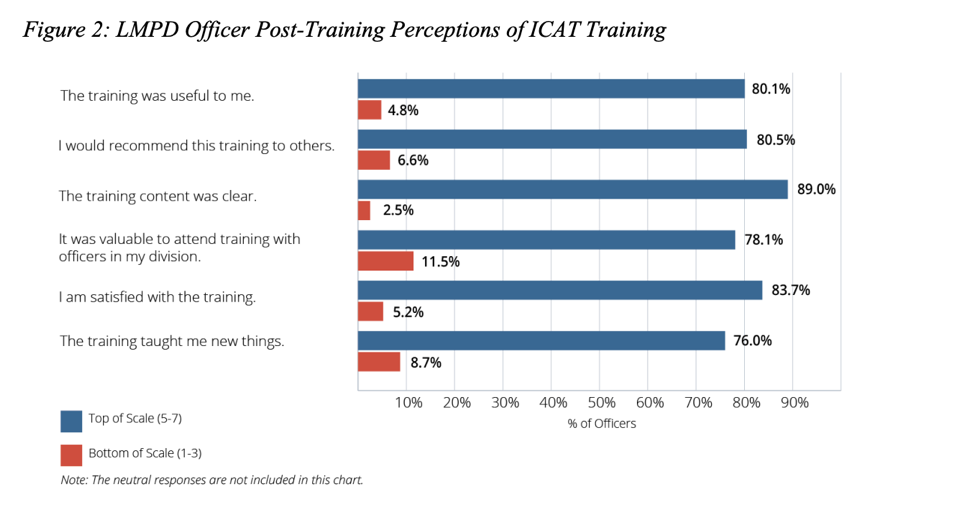

Accordingly, Engel and colleagues at the University of Cincinnati conducted a large-scale, rigorous impact evaluation of the de-escalation ICAT training program for the Louisville (KY) Metropolitan Police Department.6In their evaluation, the authors found statistically significant declines in use of force (-28%), citizen injuries (-26%), and officer injuries (-36%) and noted that they were “confident that the changes in uses of force—and the subsequent reductions in citizen and officer injuries—corresponded with the timing of the training across the various police divisions.”6 In addition, officers appeared to find the training useful and would go on to recommend it to others, even up to six months after completing the program (see Figure below).6

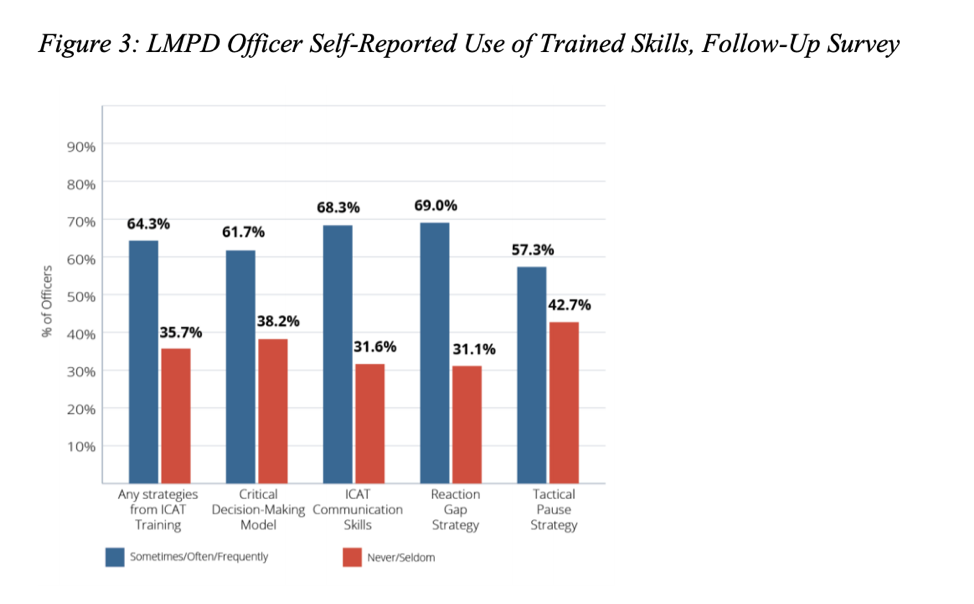

However, there was one aspect of the ICAT training that officers did not perceive positively—The CDM Model. “Analyses of post-training scores compared to follow-up scores revealed that ten of the eleven items demonstrate[d] statistically significant changes in the opposite direction than would be expected, indicating that officers reported finding the CDM less useful over time.”6 When officers were asked to self-report their confidence in using trained skills, they did not report a significant improvement immediately after or in the months after the training. This could have been a result of officers reporting high levels of confidence prior to training. However, when officers were asked to self-report their use of ICAT skills out in the field, more than 60% reported doing so in the last 60 days of work (see Figure 3).6

Although a follow-up report is forthcoming, one thing is clear—the ICAT training program may well be the only model of de-escalation empirically shown to have a meaningful impact, as strong implementation and rigorous evaluations of de-escalation and similar training programs are rare.7 Investment in evaluating training and other interventions to reduce force has been largely insufficient. As we enter into a new year, we must recognize the need to tackle one of the most pressing issues facing law enforcement and to do so with science. Only then can we build strong relationships with our communities and promoting the safety of residents and police officers alike.

Dr. Karen L. Amendola is the Chief Behavioral Scientist at the National Policing Institute and has been with the agency for 25 years serving in various capacities. She has more than two decades of experience in public safety research, testing, training, technology, and assessment. Amendola earned both her Ph.D. and M.A. in Industrial and Organizational Psychology from George Mason University, as well as an M.A. in Human Resources Management from Webster University. Karen has worked with dozens of local, state, and federal agencies. Dr. Amendola was Associate Editor for Psychology and Law for the ten-volume Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice published by Springer Verlag, New York (2014), and currently serves on the recently established American Psychological Association’s Presidential Task Force on use of force against African Americans

Sources

1 [1] https://news.gallup.com/poll/317114/black-white-adults-confidence-diverges-police.aspx

2 https://www.policeforum.org/icat-mission-statement

3 https://cops.usdoj.gov/pdf/taskforce/taskforce_finalreport.pdf

4 https://www.policeforum.org/assets/30%20guiding%20principles.pdf

5 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1745-9133.12467

7 We note that there have been other recent studies demonstrating the value of related concepts such as “social interaction training” evaluated by Wolfe, et.al., and reported on in the Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 687, January 2020. Also, work by Owens, Weisburd, Amendola, and Alpert (2018), demonstrated reductions in force as the result of a low-cost intervention to model procedural justice within the Seattle Police Department, see: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1745-9133.12337

Disclaimer: The points of view or opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the National Policing Institute.

Written by

Karen L. Amendola, Ph.D

Chief Behavioral Scientist

Strategic Priority Area(s)

Topic Area(s)

For general inquiries, please contact us at info@policefoundation.org.

Share

Strategic Priority Area(s)

Topic Area(s)

For general inquiries, please contact us at info@policefoundation.org

If you are interested in submitting an essay for inclusion in our OnPolicing blog, please contact Erica Richardson.

Share