March 27, 2018

Nola M. Joyce

Fmr. Dep. Commissioner, Philadelphia Police Department

Nola M. Joyce

Fmr. Dep. Commissioner, Philadelphia Police Department

Policing technology has moved out of the backrooms of the administration building to the core of police operations.Today police departments are using surveillance cameras, gunshot detection systems, automated license plate readers, facial recognition software, body cameras, drones, and numerous databases to prevent, respond and investigate crimes.

The near future holds even more possibilities, such as driverless patrol cars with heads-up screens, delivering information as the car patrols the streets. Augmented reality and artificial intelligence will eventually find its way into policing. Smart police uniforms could monitor and report on officers’ stress levels and the surrounding environmental conditions and provide situational awareness to supervisors about their officers.

The question is not whether this technology exists, but rather, should police use it when it becomes available to them? And, if so, how should it be used?

A paper written by Phil Lyons, Michael S. Scott, Peter Sloly and myself for the BJA Executive Session on Police Leadership explores the challenges that existing and emerging technology pose to police leaders

We think these challenges can best be addressed by developing and using a digital ethics framework and a set of guiding principles that help create digital trust. Such a framework can help police leaders and their stakeholders think through the potential effects of technologies on officers and communities, identify unintended consequences and address the use of advanced technology for public safety.

I suggest the current controversies surrounding Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube reflect, in some part, the public demand for the ethical use of technology by developers and its users.

Today, a successful business must understand the social and ethical consequences of using technology and work to mitigate negative consequences. Whereas this is arguably necessary for business, it is inescapably true for the public sector, particularly the police. Just as police leaders today work to build community trust, in the very near future they will have to be concerned with building digital trust.

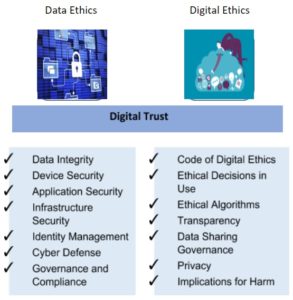

Digital trust is created when an organization has good data integrity, security and control, and its use of technology and data is governed by a code of ethics. Digital trust between the police and their stakeholders could allow for a more rapid uptake of promising technology and mitigate some of the risks associated with it.

The laws and regulations governing the capture and maintenance of crime and arrest data already provide police executives the basics of data ethics, and similar guidelines are often applied to new technology and data.

Digital ethics is broader and includes how technology and the data are used and the outcomes of that use. Transparent data and digital ethics create digital trust.

The following framework was developed by Accenture. Examples of the elements comprising data ethics and digital ethics are listed. It is a good place for police leaders to start thinking about digital trust.

Figure 1: Digital Trust Framework

As we move further into the 21 century, digital ethics and trust will become a primary issue for police. Your communities and your officers will demand the collection of data, the analysis produced, and use of the data, analysis and technology be secure and ethical.

Recent examples of how digital ethics and trust can play out are found in Chicago and New Orleans. Police departments in both cities found themselves explaining their use of algorithms to help create lists of high risk individuals. The two primary concerns emerging from these cities were around (1) transparency in what data was used and how the algorithm was generated, and (2) how the results were used.

The injudicious use of data, analytics or technology by a police department can erode the public trust and make it even more difficult to police effectively in the 21st century. Police leaders must begin now to understand digital trust and its implications to their organizations and profession.

How policing will be changed by technology is uncertain, but it is certain that police leaders will be faced with making difficult decisions around future technology. I believe that a Digital Ethic Framework can be crafted for use by police executives and their stakeholders to help guide discussions on technology. Now is the time for the profession to start thinking about these issues and building digital trust.

Nola Joyce is the former Deputy Commissioner and Chief Administrative Officer for the Philadelphia Police Department. She has 25 years of public sector experience. Joyce has previously been the chief administrative officer for the Metropolitan Police Department in Washington, D.C. and the deputy director of research and development for the Chicago Police Department. In Chicago, Joyce helped develop and implement the Chicago Alternative Policing Strategy (CAPS). CAPS was one of the most studied community policing initiatives in the country and was a nationally recognized community policing model.

Disclaimer: The points of view or opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the National Policing Institute.

Written by

Nola M. Joyce

Fmr. Dep. Commissioner, Philadelphia Police Department

Strategic Priority Area(s)

Topic Area(s)

For general inquiries, please contact us at info@policefoundation.org.

Share

Strategic Priority Area(s)

Topic Area(s)

For general inquiries, please contact us at info@policefoundation.org

If you are interested in submitting an essay for inclusion in our OnPolicing blog, please contact Erica Richardson.

Share